THE GREAT SEALS

of MINNESOTA

1849

The story begins with the establishment of the Minnesota Territory in 1849, which created a need for a seal to stamp official territorial documents ... Alexander Ramsey, the territorial governor, initially used his own design. His first version was a sunburst and the motto "Liberty, Law, Religion, and Education." It was soon replaced by a seal showing a Native family handing a ceremonial pipe to a settler. Ramsey wanted the seal to emphasize a peaceful coexistence between white settlers and Native Americans ...

But Henry Sibley, an ambitious young fur trader who represented the territory in Congress, decided to commission a few alternatives. It was popular at the time for territorial seals to celebrate the idea of manifest destiny — that white Americans were ordained by God to settle across North America. Army engineer and draftsman John Abert drew up four designs for Sibley, one of which depicted a farmer pushing a plow in the foreground while a Native American man rode on horseback toward the rising sun [sic; photo above left]. Sibley commissioned a watercolor version of that image from Seth Eastman, a U.S. Army captain who served several stints at Fort Snelling and had become known for his paintings of Minnesota landscapes [photo above right].

When Ramsey saw the painting, he suggested replacing a tree stump near the farmer with a teepee to represent Native American life in the state. "Even Alexander Ramsey was saying: 'Maybe we are taking this settler imagery too far" ... Henry Sibley just kind of ignored him and doubled down." Sibley added an axe and rifle instead of a teepee and a Latin motto that, roughly translated, meant: "I wish to see what is beyond." That design was accepted by the territorial Legislature in 1849, becoming Minnesota's official seal. The next year, Seth Eastman's wife, Mary, wrote a poem about the seal that left little doubt about the message she believed it was sending. Writing the "red man's course is onward," Mary continued: "We claim his noble heritage, / And Minnesota's land / Must pass with all its untold wealth / To the white man's grasping hand."

(From B. Bierschbach, Star Tribune, Nov. 3, 2023; complete poem here)

1849-1858

The first of Minnesota's official seals was created in 1849 for the Minnesota Territory. It symbolized a "Manifest Destiny" mindset, i.e., the white man taking over the frontier as the U.S. spread, driving the Indians westward (see column at right). There was one obvious problem: The Indian – who was supposed to be heading westward into the sunset – appeared to be heading eastward into the sunrise, because the seal was engraved in reverse (see reverse image of original dye, above). The seal was based on a watercolor (shown further above) by Captain Seth Eastman, an astute artistic observer of frontier life. His wife, Mary Henderson Eastman, wrote a poem about its meaning.

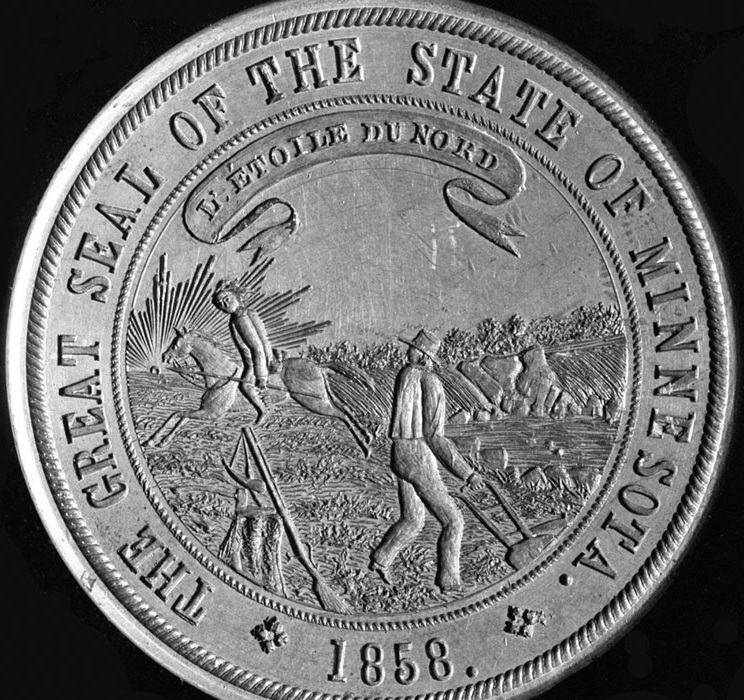

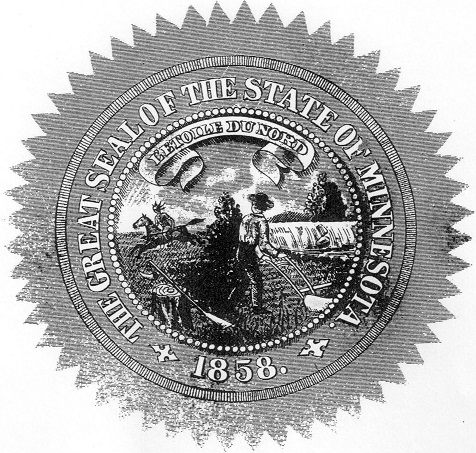

1858-1881

After statehood, both legislative chambers

apparently adopted a new seal design in 1858, which portrayed harmony between the white man and Indian (above, left). However, Governor Henry Sibley

never signed this bill. He instead replicated the territorial seal – but reversed its image so the Indian rode westward, as originally intended (above, right; image of original dye from MHS collections). He also changed the previous Latin motto to "L'Étoile du Nord" ("The North Star"), representing Minnesota as a guiding light for the Union. He apparently rendered the motto in French as a tribute to the legendary voyageurs. Sibley's design was endorsed by the legislature in 1861, under Governor Alexander Ramsey.

1881-1971

The state seal was re-cast in 1881, after the original dye was evacuated and misplaced during a fire at the capitol. (The original seal was retrieved in 1901, and turned over to the state historical society; but was misplaced again in 1984.)

1971-1983

Because of complaints about the seal's portrayal of the white man's takeover of the

frontier from the Indian (see column at right), a new version of the seal was authorized by the Secretary of State in 1971. Although it had no legal standing, the Indian was replaced by a "white rider." This seal was apparently promoted and employed by the office of the Secretary of State, but was never used on the state flag.

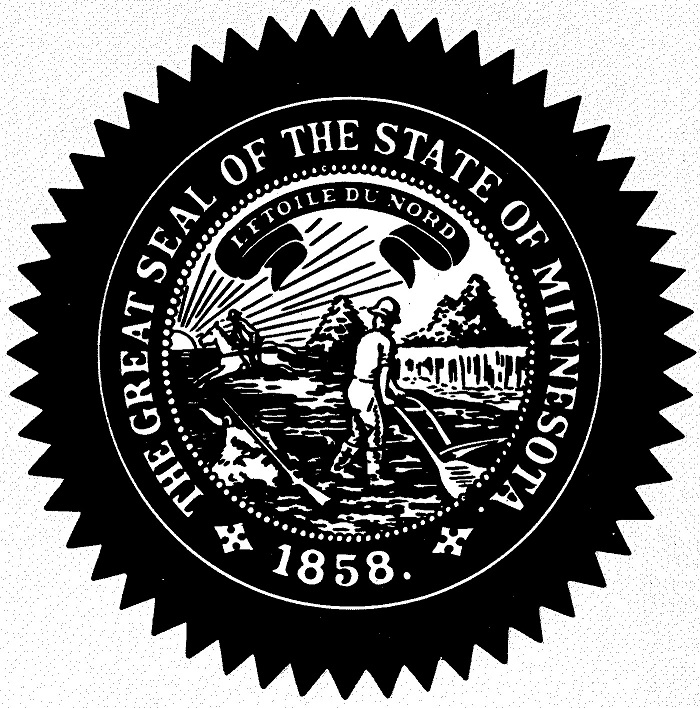

1983-present

In 1983, the legislature modernized and standarized the design of the seal. To respond to

objections to previous designs (see column at right), the Indian

rider is now portrayed as trotting southward while facing the white

man, rather than fleeing westward from the advance of the white

man. The design was drafted by Jacki Bradham, a state employee.

SOURCES:

Briana Bierschbach, "What's the story behind Minnesota's controversial state seal?" Minneapolis Star Tribune, Nov. 3, 2023

Heather Brown, "How Did 'L’etoile du Nord' Become The State’s Official Motto?" WCCO-TV News, May 7, 2019

Robert M. Brown,

"The Great Seal of the State of Minnesota." Minnesota History 33 (1952): 126-129

Mary Henderson Eastman,

"The Seal of Minnesota" [poem], Minnesota Pioneer,

Feb. 20, 1850, p. 2;

also here

Seth Eastman, “Design for Minnesota Territorial Seal,”, watercolor, AV1984.331.1 (Accession Number), Minnesota Historical Society

Nancy Eubank, "The Dakota," Roots 12:2 (Winter 1984). St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society. 4

William W. Folwell, History of Minnesota, 1:459-462; 2:25-26,

357-361. St. Paul, 1924

"The Great Seal of the State of Minnesota." Minnesota Historical Society: Collections Online, photoprint (locator no. FM6.64 p4, negative no. 296)

Jeffrey A. Hess,

"State Seal." Minnesota Almanac, in

Roots 13:1 (Fall 1984). St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society. 21-23

"Minnesota's New State Seal," Minneapolis Star Tribune, Nov. 11, 1983

“State Seal,” Minnesota Secretary of State (Official Website)

Lori Williamson, “Minnesota Territorial Seal, 1849,” Collections Up Close, Minnesota Historical Society (official weblog), July 2, 2014

MORE:

Deborah L. Gelbach, From This Land. Northridge CA, 1988. 29-31

John Biewen, “Little War on the Prairie,” Resilience.org ("Seeing White," episode 5, June 10, 2020, at 1:00:18; originally published by Scene on Radio and produced for This American Life, November 23, 2012)

Kevin Dragseth, 2020, "The Great Seal of Minnesota," in "Who made Minnesota the Gopher State?", TPT Originals

William Convery, "Minnesota State Seal," MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society, 2023

|

THE GREAT SEAL

CONTROVERSY

David Gillette,

"Redesigning Minnesota’s State Flag,"

TPT Almanac, Twin Cities Public Television, March 28, 2018

(Interview with Adam Scher, Minnesota Historical Society, at 00:01:20)

[Scher:] "The flag image, which is based on the state seal, goes back to before Minnesota was a state, when it was a territory. Seth Eastman, who was an artist and also served in the military, was stationed at Fort Snelling during the territorial period, and he rendered a sketch which became the inspiration for the territorial seal."

[Gillette:] "This seal, which did later become our state seal, was flipped horizontally from the original watercolor, to make sure the Native American was riding away into the west."

[Scher:] "This was 'Manifest Destiny' – that white settlement was dislocating Native Americans – and so people have to understand how this image was created in context."

Nancy Eubank, "The Dakota."

Roots 12:2 (Minnesota Historical Society, Winter 1984), p. 4.

In the 1840's, when American settlers reached Minnesota, the Dakota lived along the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers on prairie lands that were ideal for plowing and planting. The rich land made white farmers eager to use it in the way that seemed best to them. The settlers felt that if the Indians did not want to farm the land they should move away, whether they wanted to or not. The Dakota did move on, forced by the U.S. government to give up their hunting grounds. This sad part of Minnesota's past – the Indians' loss of their land – is pictured on the state seal. In the foreground of the seal a farmer plows his field, while in the background an Indian on horseback gallops away. Mary Eastman, the wife of the soldier-artist Seth Eastman who helped design the seal, wrote a

poem about its meaning:

Give way, give way, young warrior,

Thou and thy steed give way;

Rest not, though lingers on the hills

The red sun's parting ray.

The rock bluff and prairie land

The white man claims them now,

The symbols of his course are here,

The rifle, axe, and plough.

Jeffrey A. Hess, "Minnesota Almanac."

Roots 13:1 (Minnesota Historical Society, Fall 1984), p. 21-22.

When Minnesota became a territory in 1849, its lawmakers picked a committee to design a territorial seal. The committee chose a design that showed an Indian family offering a peace pipe to a white settler. But the territorial legislature did not approve this design. Many of the lawmakers believed that there would never be peace in Minnesota until all the Indians had moved westward out of the territory. Since the legislators could not agree on a design, they left the decision to Governor Alexander Ramsey and Henry H. Sibley, Minnesota's delegate to Congress. Sibley suggested using a picture drawn by Captain Seth Eastman, an artist and commanding officer at Fort Snelling. This design was accepted by the legislature and became the seal of the Minnesota Territory. Eastman's picture shows a white settler plowing a field beside the Mississippi River near the Falls of St. Anthony. His ax and gun rest on a tree stump in the foreground. In the background an Indian on horseback, spear in hand, gallops away into the sunset [...] Then during the 1960's, some people began to question whether it was a good state symbol. Citizens are supposed to be proud of their state's symbols. But how could Minnesota Indians be proud of a seal that seemed to say they were not wanted in their own state. In 1968 the Minnesota Human Rights Commission asked the state government to design a new seal that all Minnesotans could be proud of.

“Lawmakers push to redesign Minnesota state flag and seal”

Associated Press, March 24, 2022

The seal … fails to come to terms with Minnesota’s history of violence against Native Americans, said Kevin Jensvold, tribal chairman for the Yellow Medicine Dakota of the Upper Sioux Community. “You see a very distinct line that is created by the plowed fields right in the middle showing that there is a division between the European at that time and the Indigenous person, and basically pushing them off into the sunset,” he said. “That way of life, that genocidal attempt to destroy our culture is depicted on that flag” … Jensvold called the [seal/flag] redesign overdue, and said Minnesota should follow Mississippi’s lead in promptly changing a flag that its residents find racially offensive. “If we are viewed in the context that we are going to continue to allow that to be displayed at the expense of the Dakota people, … [then lawmakers] need to justify that.”

Governor Tim Walz

Press Conference, June 10, 2020 (excerpt, transcript)

"This question around symbolism is important … Yesterday, I had a long conversation with our sovereign tribal leaders. And [a Dakota leader] says, every time he watches me and I stand in front of the seal of Minnesota, it brings pain to him. These are conversations that Minnesotans – I hear it get pushed off as frivolous or political correctness – these are historical pains that … can inflame emotion …. Now we better start having those honest conversations."

Grant Moos, "New Wave"

(Minnesota Monthly, November 1989, p. 23-24.)

There is evidence that the state seal, upon which the flag is based, is somewhat illegitimate. The bill written to establish the seal was never signed by the governor in 1858, although it was given official sanction three years later. The legislature had approved a completely different design, one of Indians and whites living in harmony – a concept that then-Governor Henry Sibley felt was untenable. Sibley has been accused by historians of 'mislaying' the design that lawmakers approved and replacing it with the territorial seal he helped design. To this day Sibley's seal remains the basic design.

"Changing State Seal Expensive,"

(Saint Paul Pioneer Press, November 28, 1968, p. 21)

by Robert Whereatt, Staff Writer

It would be rather expensive to Minnesotans to cover a dark part of the state's history by changing the Great Seal of the state. The Minnesota Human Rights Board has recommended a new seal be designed because, the board said, the current seal 'illustrates

a dark part of our history.' The seal shows a white man plowing in the foreground, and an Indian in the background riding toward a setting sun. The white man has a musket and powderhorn nearby. The Indian carries a spear. The rendition of the state's past apparently offends the state board which has suggested a new seal 'which will demonstrate and promote Minnesota's current attributes and its potential for future development.'

But changing the seal would require more than a simple redesigning of the seal now guarded zealously by its custodian, Secretary of State Joseph Donovan. About 35,000 notaries public in the state certify documents with notorial seals which have the state Great Seal design in their centers, according to Donovan. The current cost of replaicng these seals is about $8.50 each. So it would cost almost $300,000 for the notaries to get new seals.

In addition, the Great Seal is in the center of the state flag. The major manufacturer and distributor of state flags, a Minneapolis firm, estimates conservatively that current value of large state flags sold over the past 11 years is not less than 100,000. The Great Seal is more ubiquitous than just flags and notarial seals. County and state officers have the seal at the center of their official seals. Official state stationery has the seal on it and the paper used in bills enacted by the legislature has the seal imprinted in it. The seal is imprinted in paper used for bonds issued by the state and in blank certificates of various kinds.

Gov. Harold LeVander was asked about the great Seal controversy Wednesday. 'It's not a matter to be overly concerned about,'

he said. He implied the Human Rights Board could better spend its time in other areas. 'It's been in existence a long time,' LeVander said. 'It's difficult to change history or rewrite it.'

"Is Bad Art Good History?"

(Minneapolis Star, November 26, 1968, p. 7A)

by Austin C. Wehrwein of the Editorial/Opinion Staff

The Minnesota Board of Human Rights is on the warpath against the Great Seal of the State of Minnesota, re-opening thereby a 119-year-old legal dispute.

What worries the board about the seal, which is a little like a state trademark, is that it 'depicts warfare' between the early white settlers and the red men, and 'places the Indian in a derogatory light.' Human Rights Commissioner Frank Kent, a black man, will ask the legislature to think about authorizing a new seal.

As civil rights issues go, this is rather esoteric. The seal we have is, without doubt, a horrible example of 19th century government art, but the board had no need to defer to the seal's 'historic significance.' In 1849 its almost identical predecessor was ridiculed as depicting 'a scared white man and an astonished Indian' and 'a man plowing one way and looking another.'

Gov. Sibley selected the seal's motto, 'L'etoile du Nord' (North Star). William Watts Folwell's History of Minnesota says

one newspaper 'poured out vials of sarcasm upon "Mister" Sibley for selecting a motto from Canadian French patois, the only French known to him, and one conveying no appropriate sentiment.'

In 1860, the Minnesota attorney general said the seal had been sanctioned by usage but implied that Sibley had adopted the design without authority. In 1861, the legislature, to cure any illegality, passed a law that said, for sure, the great seal was the great seal.

The seal, of which the secretary of state is the 'custodian,' is supposed to appear on all 'official' documents, including the governor's stationery. This is a relic of the time when seals were used to authenticate documents, a practice akin to certifying checks. In the old common law, a seal had to be a blob of wax on the document on which an impression of a design was made.

The battle of the Minnesota seal began with territorial Gov. Ramsey who cooked up his own, a sunburst with the motto, 'Liberty,

Law, Religion, and Education.' Then he asked in 1849 for a law to authorize an official seal, apparently suggesting a design that showed an Indian family welcoming a white man with a peace pipe to symbolize inter-racial friendship, precisely the sentiment the Rights Board would prefer.

However, the legislature rejected the particular design, while authorizing a seal to be selected by Sibley, then a delegate to Congress, and Gov. Ramsey. The design we have today took its first form from sketches by Col. John James Abert that were redrawn by Capt. Seth Eastman.

That seal depicted a farmer, hand on plow, his musket leaning on a stump. He is watching an Indian, armed with a lance,

riding bareback into the sunset, with St. Anthony Falls in the background. Sibley is credited with providing the motto, Latin

for 'I Wish to See What Lies Beyond.' Whatever it was supposed to mean, one Latin word was misspelled by the engraver.

The version we have today is virtually the same, except that [...] the motto is 'The North Star.' It was adopted by the new State of Minnesota in 1858. Or rather by Sibley, who was by then governor [...]

In the absence of artistic directions from the legislature, Gov. Sibley played with the territorial Seal. The newspaper that objected to his North Star motto also said nastily that he should have designed a new seal [...]

But objection to the design died until the 1968 Human Rights Board revived it.

The present Custodian of the Great Seal, Secretary of State Joseph Donovan, said he wanted to 'analyze and digest' the new

seal proposal. Said he of the frightened farmer and fleeing red man, 'I don't know if you can eradicate and erase history to bring it up to date to conform to issues of the time.'

|